We write and talk a lot about ‘sweetened fibres’. But what is it? In this article, we take a closer look (literally) on sweetened fibres, and answer some questions: What is sweetened fibres? What are they made of? And how does it work?

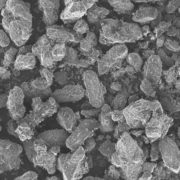

The large picture at the top of this article is taken by a scanning electron microscope. It shows sweetened fibres at forty times magnification. Already in this magnification, it is possible to see what makes sweetened fibres unique. Do you see it? If not, read on. In this article, we will take an even closer look at sweetened fibres. But let’s start from the beginning.

Food and beverage producers’ dilemma

Too much sugar is bad for health. Therefore, there is a growing demand from consumers, and increased pressure from legislators, to reduce the amount of added sugar in food and beverage. But at the same time, consumers are unwilling to give up the sweet taste and good mouthfeel that sugar gives. This is the food and beverage producers’ dilemma in sugar reduction.

It can be tempting to replace the bulk and sweetness of the removed sugar with other ingredients (e.g. fruit juice) that fill the sugar’s place (literally) and taste almost as sweet. But if these ingredients contain close to as many calories per gram, it’s like painting lipstick on the pig.

Don’t make your brand a disservice

Brands, which boast that they add less or no sugar, but have replaced it with something almost as calorie-rich, do consumers a bad turn and themselves a disservice.

After all, it is not less sugar that consumers are looking for. It is its negative impact on health that they want to avoid. But the positive health effect isn’t forthcoming if what replaces sugar has the same calorie content or the same effect on blood sugar levels.

Food and beverage producers who substitute sugar in this way, of course do so with the best of intentions. But the question is whether sensational writers on blogs and evening newspapers take this into account when they get sight on what maliciously can be described as a food bluff.

So the service that food and beverage producers think they are doing, when they exchange sugar for something else, can prove to be a disservice for their own brand.

So what is the problem with sugar?

The problem with sugar is that it is not as sweet as one might think.

It takes a lot of sugar to achieve the sweet taste in food and beverage. And since a lot of sugar also takes up a lot of space — contributing to both volume and weight — sugar works as a filler. It gives bulk. The same goes for glucose syrup, high-fructose corn syrup, maltitol and a host of other sweetening ingredients. Since these sweeteners give bulk, they are called bulk sweeteners.

But bulk sweeteners don’t just give us volume and weight. They also provide energy and affect blood sugar levels. Sugar gives 4 kcal per gram and has a GI of 97 (relative to white bread). Glucose syrup gives just as many calories and even higher GI.

This is the real problem. Bulk sweeteners provide sweetness and bulk, but at the price of too many calories and a rush in the level of blood sugar.

More sweetness for fewer calories

Of course, the solution is to use ingredients that provide more sweetness for less calories.

Take aspartame, for example. It provides as many calories as sugar. But it is two hundred times sweeter. Thus, only 0.5 grams of aspartame is needed to give the same sweetness as 100 grams of sugar. And 0.5 grams of aspartame contains only 2 kcal, while 100 grams of sugar contains 400 kcal.

A problem with aspartame is that it is entirely synthetic. And many consumers are hesitant about artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, acesulfame K and sucralose.

Fortunately, there are high-intensity sweeteners of natural origin, such as reb A and reb M, which are steviol glycosides extracted from the plant stevia.

Is this the solution to the food and beverage producers’ dilemma?

New challenges

With high-intensity sweeteners come new problems: They do not taste like sugar (except reb M) and do not contribute to bulk and texture; three grams of steviol glycosides give the same sweetness as one kilogram of sugar but leaves a massive void. What should the other 997 grams of sugar be replaced with?

Food and beverage producers with required niche competence in-house can find product-specific solutions by experimenting with different ingredients. But it takes time and costs money. Is there no better solution?

The ideal solution

Let’s stop and summarize our insights.

Food and beverage producers’ dilemma in sugar reduction is that consumers both want to remove sugar and retain the sweetness and mouthfeel of it. Both eat the cake and have it.

In theory, the solution is to replace sugar with ingredients with less calories but the same sweetness and mouthfeel. But in practice, it is more complicated.

Common bulk sweeteners have volume, weight and mouthfeel that reasonably match sugar. But so does their calorie content. So they go away.

High-intensity sweeteners do not contribute any calories. But the same can be said about their ability to provide volume, weight and mouthfeel. Thus, they cannot be used alone. They must be supplemented with other ingredients that fill in and give the same texture as the sugar. It sounds simple but is very difficult even for experienced and knowledgeable food and beverage technicians. Therefore, it takes a long time and costs a lot of money.

Imagine if there was a bulk sweetener with the same volume, weight and mouthfeel as sugar, and with zero calories. It would be the ideal solution.

Unfortunately, there is no perfect solution. But with sweetened fibres, you come as close as possible.

Close to the ideal solution

Sweetened fibres is a new kind of bulk sweetener that

- is as sweet as regular sugar,

- contributes to the product’s taste and mouthfeel as regular sugar,

- has the same volume and weight as regular sugar,

- can be transported, stored and used as regular sugar,

while

- having fewer calories than regular sugar, and

- have less impact on the level of blood sugar than regular sugar.

As you can see, sweetened fibres is close to the ideal solution. But we make no bones that it is impossible to reach all the way.

Caveats

Sweetened fibres are sugar-like, but not identical to regular sugar. Therefore, there are slight differences in taste and mouthfeel that may require some fine-tuning of recipes to reach full perfection.

And above all, sweetened fibre is not entirely calorie-free. How much there are depends on the composition, which in turn is dictated by how they are to be used. But in common, the amount of calories is significantly less than in regular sugar.

What sweetened fibre are made of

Sweetened fibres contain nothing that is not already used by the food and beverage industry. They consist of dietary fibres, sugar alcohols and high-intensity sweeteners. These play different roles in the sweetened fibres.

Sugar alcohol has several functions. First and foremost, it contributes to bulk; it takes place. It also helps to give the right taste and mouthfeel. Not least, it is used to mask off-flavour and aftertaste of the other ingredients. It’s also sweet – but not as sweet as sugar. In some applications, sugar alcohol may also replace some other properties of sugar.

High-intensity sweetener is used to compensate for the insufficient sweetness of sugar alcohol. The quantities are so small that they don’t practically contribute to bulk or mouthfeel. So its only function is to provide sweetness.

Dietary fibres main job is to literally hold on to the other ingredients. It is this retaining function that makes sweetened fibres into sugar-like grains. Besides, fibres contribute to bulk and mouthfeel. Some fibres also have flavour and sweetness that helps to shape the right sweet taste.

Plant-based

It may be worthwhile to stop for a moment and note that all ingredients found in sweetened fibres are plant-based.

Fibres are extracted from plants (for example inulin) or is made from starch (for example dextrin, isomaltooligosaccharides and polydextrose), which in turn comes from potatoes, wheat, corn, cassava and other starchy crops.

Sugar alcohols are also produced from starch (for example maltitol, sorbitol and erythritol).

Last, we have high-intensity sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners can be used. But why use them, when steviol glycosides are found naturally in the stevia plant.

What makes sweetened fibres unique?

What makes sweetened fibres unique is the way they are made.

Compare with a bakery. Most bread contains flour, water and yeast. The secret behind the taste is not the ingredients, but how they are baked into bread with a unique character and taste.

In the same way, we ‘bake’ sweetened fibres from dietary fibres, sugar alcohols and high-intensity sweeteners. The result is grains similar to sugar grains. This is what makes sweetened fibres unique.

Each grain consists of sugar alcohol, high-intensity sweetener and dietary fibres., formed into a coherent unit. This means that sweetened fibres in the form of powder or granules are entirely homogeneous. And that, in turn, means that the constituent ingredients do not layer during transport and handling and that they do not distribute unevenly in production. The graininess also contributes to the mouthfeel.

Sweetened fibres in close-up

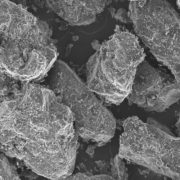

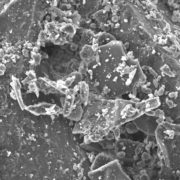

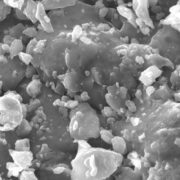

The pictures above come from a scanning electron microscope (SEM). They show sweetened fibres in 40, 100, 1,000 and 5,000 times magnification. Click on the pictures to see them better.

In 40 and 100 times magnification, what look like boulders are fibres. In the scanning electron microscope, they look smooth because they do not have flat surfaces like crystals. But in fact, they consist of tightly packed platelets that can be seen at 5000 times magnification.

We have a patent-pending for a manufacturing method that embeds sugar alcohol and high-intensity sweetener in between the platelets. The result is fibres that literally hold on to the sweet ingredients, as can be seen at 1,000 times magnification. That’s why we call them sweetened fibres.

Some of the retained ingredients protrude from the fibres. In 40 and 100 times magnification, it looks like cobwebs or frost on the ‘rock bumps’.

Areas of application

If we ignore the calories, sugar is actually a fantastic ingredient. In addition to tasting sweet and contributing to the pleasant mouthfeel, sugar has a wide range of useful properties: enhance taste and aroma, thicken and stabilize, preserve, give colour, lowering freezing point, and keep moisture. Sugar is simply a universal ingredient.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to create a corresponding universal ingredient in the form of sweetened fibres. But it is possible to develop sweetened fibres that are ‘turnkey’ solutions for different application areas.

Turnkey sweetened fibres replace sugar one-by-one. One kilogram of sugar is replaced by one kilogram of sweetened fibres – with no or minimal fine-tuning of the recipe.

Eureba

We develop, produce and market sweetened fibres under the brand EUREBA®. At the time of writing (April 2020) we have created turnkey sweetened fibres for the following applications:

- Bread and pastries

- Almond paste

- Chocolate

- Caramel and carbonated sauces

- Protein bar

- Ice cream

- Fruit preparations for dairy products and frozen desserts

- Soups and sauces

Here you can see our range of sweetened fibres and order product sheets.

Your turn: Try sweetened fibres

Do you want to try sweetened fibres? Fill out the form below, and we will send you a sample. The offer is primarily aimed at those who work professionally with food and beverage at a producer or distributor.

[mautic type=”form” id=”9″]