Stevia – the sweet plant that challenged the giant companies

Product development • How can a single herb threaten a whole industry? There is a substance called steviol glycosides in the stevia plant, three hundred times sweeter than sugar and completely without calories. This unbeatable combination posed a threat to the artificial sweeteners monoply controlled by the food and beverage industry giants in the 80s and 90s. It was David versus Goliath.

In the beginning of the 1980s stevia found itself in the spotlight. Many quickly understood that its good qualities would definitely benefit consumers. Just imagine, being able to indulge in sweet foods and drinks without the guilt.

But the big producers of sugar and synthetically manufactured sweeteners had other plans.

Their business was threatened by this little contender. Consequently they were not exactly helpful in getting stevia approved by the various food safety authorities. Some critics even say that they actively worked against the approval.

But the sweet little plant won – like David against Goliath. This is the story of how it all happened.

Sweeter than sugar

For more than 1,500 years the natives of Paraguay have used stevia as a natural sweetener. When the leaves are dried they are thirty times sweeter than sugar.

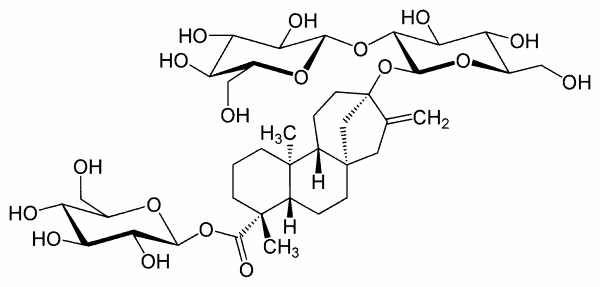

The substances that are responsible for the sweetness are called steviol glycosides and can be extracted from the plant in about the same way as sugar is extracted from sugar beets. The result is a powder that is 300 times sweeter than sugar.

However, unlike sugar, steviol glycosides do not contribute any calories. So there won’t be any calories turning into fat. And it doesn’t raise the blood sugar, or cause tooth decay.

Resistance to stevia

In the early 1990s studies took place, which spoke against stevia. Animal testing hinted at steviol glycosides possibly breaking down into substances that might be cancerogenic. Other studies showed it affected the fertility in female rats.

Some of the studies were criticised for being too small or having insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding side effects in humans. And it was thought that the studies had been commissioned by the artificial sweetening industry. Despite this the studies were frequently used as arguments against stevia.

The door was firmly shut on stevia in the West. Neither the plant nor steviol glycosides were approved for use.

In Japan there was another take on the situation. Stevia was approved in the beginning of the 1970s and by the 1980s they already had a market share in excess of 40%.

A new chance for stevia

And then things changed. Patents for several sweeteners expired, making it possible for Chinese manufacturers to compete at lower prices. The market was flooded with cheap products.

For the companies whose patents had expired profits sank, and so did their interest in artificial sweeteners. Previously uninterested in the plant, they now started to wake up to stevia. But how could they make use of its sweetness?

Steviol glycosides – ”big business”

You can’t patent a plant that has been known for centuries. Anybody can plant, grow and sell it. But, if you can find a hitherto unknown substance in the plant you have a possibility to patent it as a solution to a technical problem.

The substance Rebaudioside A (often abbreviated to Reb A) was discovered in stevia. It is one of several glycosides which gives stevia its sweet taste. Coca-cola patented it in 2007, along with 23 other stevia related patents.

Suddenly major players like Coca-cola and their partner Cargill wanted steviol glycosides approved as an additive. As the companies prepared to move away from sugar, aspartame and other sweeteners, in favour of the tough little contender stevia.

In December 2008 the sweetening agent Reb A was approved as a food additive in the US by the Food and Drug Administration, FDA. France caught on in 2009, and in 2011 it was approved for use in the whole of EU.

A safe choice

In the EU it is today allowed to sell the leaves from the plant as tea, herbal tea or fruit infusion. In other cases it’s use is subject to EU Food Safety (EFSA) approval for each particular food category.

Steviol glycosides however, are approved as an additive in limited amounts and in certain foods.

But what about the risk of cancer? And diminished fertility? For over fifty years the Japanese have used and enjoyed their stevia. None of the studies carried out since its approval have been able to show stevia causes either of these side effects.

Today stevia and steviol glycosides are no longer controversial.

Please, share this article if you liked it.

[et_social_share]