Saccharin – a guide to artificial sweeteners

Product development • The world's first artificial sweetener was discovered in 1879 and had its breakthrough during the First World War. Today, saccharin is somewhat outdated, competing with younger models.

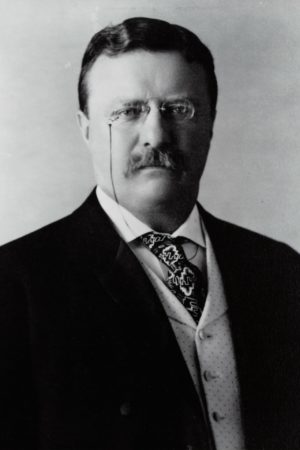

In our series ‘Guide to artificial sweeteners’, we have come to saccharin, which has a dramatic story that could fit right into a movie. During its long history, it has received much criticism and was even banned in the 1990s. The question is, is there any truth in President Roosevelt’s famous statement: ‘Anyone who says that saccharin is dangerous is an idiot!’

What is saccharin?

Saccharin is the world’s first artificial sweetener. It went on sale in Germany in 1885 and made a great impact during the First World War when the shortage of sugar was great.

Its systematic name is 1,1-dioxo-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one. Its chemical name is C6H4SO2NHCO. Saccharin has an E-number: 954.

Saccharin is 500 times sweeter than sugar and is often used in combination with aspartame or cyclamate. It can withstand heat and has a long shelf life. Saccharin is often used in baked goods, jams, jelly, chewing gum, canned fruit, candy, dessert toppings, and salad dressings. It can also be found in cosmetic products, including toothpaste and mouthwash. Additionally, it’s a common ingredient in medicines, vitamins, and pharmaceuticals.

Have you used sugar in the bread?

Saccharin was discovered in 1879 by Constantin Fahlberg, who conducted research under the direction of Ira Remsen. Fahlberg would become both rich and famous thanks to saccharine, while Remsen had to wait a long time for his recognition.

It all started with an American company being accused of having coloured sugar brown (to get a lower sugar tax due to poorer quality). The company hired the chemist Fahlberg as an expert witness. The lawsuit dragged on, and Remsen brought Fahlberg into his team.

One day when Fahlberg was having dinner, he discovered that the bread tasted sweet. He accused his housekeeper of baking bread with sugar. The housekeeper, for her part, accused Fahlberg of being an unscrupulous employer. After a brief altercation, Fahlberg had to admit the housekeeper was right because it was not the bread that was sweet, but his hands. And not just the hands. Both his arms tasted sweet! How could that be?

He quit eating and rushed back to the laboratory where he immediately began licking all the glasses and bowls until he found the source of the sweetness.

Obtained a patent in his own name

After testing his ‘anhydro-ortho-sulfamine-benzoic acid’ (later renamed by Fahlberg to Fahlberg’s saccharin) on some rabbits who did not complain, Fahlberg travelled to Germany and took out a patent on the sweetener in his own name and started a factory in 1885.

Remsen never forgave this betrayal. Shortly before his death, he said: ‘I did not want his money, but I did feel that I ought to have received a little credit for the discovery’.

Fahlberg became rich on his saccharine, which caught the eyes of the European sugar barons who saw their own sales fall. Politicians in Germany and other European countries also wanted to keep up the price of sugar, as the tax on sugar was a major source of income during this time. Several laws and restrictions were enforced. This led, among other things, to saccharin only being sold in pharmacies (to diabetics) and for the state to determine the price. In practice, saccharin was banned, and the price of sugar rose sharply.

This led to extensive smuggling of saccharin. There was, in fact, one country left where it remained free: in neutral Switzerland. They did not have a tax on sugar; it would be a disadvantage to their chocolate production. Therefore, they didn’t perceive saccharin as a threat that should be limited. Among other things, smugglers melted saccharin into wax and made candles of it, which they could then smuggle across the border to sweet-loving neighbours.

Soon came World War I, and there was a shortage of sugar. Politicians who previously wanted to ban saccharin now hailed it as a gift from the gods. Saccharin was released ‘freely’ and experienced a time of greatness that lasted until the end of World War II.

The roar of Roosevelt

In the United States, President Theodore Roosevelt played an important role in the survival of saccharine. In the early 20th century, resistance to food additives such as cocaine, opium and cannabis grew. The chemist Dr Harvey W. Wiley ran a campaign to create laws against additives and especially wanted to ban saccharin, which he considered to be especially dangerous.

When he came to President Roosevelt, he made the mistake of speaking before being addressed. It’s not a smart tactic when socializing with kings or presidents. Roosevelt became so angry that he finally shouted: ‘Anyone who says that saccharin is harmful to health is an idiot!’

The very next day, Roosevelt put together a referee board by consulting scientific experts to evaluate once and for all the health risks associated with saccharin.

The leader of the group and who thus had the power to ban saccharin was Remsen, the man who didn’t get the credit for his discovery. He now had an excellent opportunity to take revenge on his old colleague Fahlberg.

But Remsen was always on the side of science. He didn’t let his emotions control him. He went through all the research that was available and came to the conclusion that saccharin was safe. Remsen’s old colleague Fahlberg got a green light to sell saccharin in the USA and became – if possible – even richer. In 1959, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) ruled that saccharin should be viewed as GRAS (Generally Recognised as Safe).

Is saccharin safe?

In 1997, the Canadian Minister of Health told the WHO that Canada would ban saccharin due to test rats having bladder cancer. Among other things, this led to Coca-Cola and Pepsi seeing their light products banned. The research to which the Minister of Health referred was not complete and the researchers distanced themselves from his statement. However, the news spread widely, and the United States also decided to ban saccharin until the matter was investigated.

The FDA eventually launched a press release that showed that people would have to drink 800 bottles of sugar-sweetened soda every day during a lifetime to get as much as the rats in the Canadian study.

After 18 months, the United States released its ban, but by then the damage had already been done. Saccharin got a bad reputation that it did not manage to shake off.

Does saccharin affect the intestinal flora?

An Israeli study published in 2014 in the scientific journal Nature showed studies on rats that saccharin, sucralose and aspartame can affect the intestinal flora, which in turn can raise the levels of glucose in the blood. The same study was done on seven people. Four of them had poorer glucose sensitivity. There is too little evidence to draw any definite conclusions. More studies are needed, the researchers say. It is worth keeping an eye on future research.

What ADI does saccharin have?

ADI stands for acceptable daily intake and shows an upper recommended level for how much to eat of a certain substance. The ADI for saccharin is 5 mg per kilogram body weight. The ADI for cyclamate is 7 mg. For aspartame, it is 40 mg.

Benefits of Saccharine

- It is 500 times sweeter than sugar.

- Saccharin is stable when heated and in an acidic environment.

- It has a long shelf life.

- It contains no calories.

- It has been around for a long time and has been tested in many studies.

Disadvantages of saccharin

- It has a bitter or metallic aftertaste, especially at high concentrations.

- Although it is classified as safe, many organizations recommend that children and pregnant women should not eat it.

- It can cause allergic reactions such as headaches, difficulty breathing, diarrhoea and skin problems.

- For periods, it has only been sold with a warning label.

- Sackarin has a half-baked reputation and has at times only been sold with a warning label.

A Summary

Saccharin was discovered in 1879 and is the world’s first artificial sweetener. It had its heyday during the First and Second World Wars when there was rationing on sugar. It was also popular in the 1960s and 1970s when light beverages had its breakthrough. Since then, its star has fallen due to bad publicity, mandatory warning texts and bans.

The future is natural

Steviol glycosides (colloquially called stevia) are naturally sweet substances found in the stevia plant.

Steviol glycosides are extracted from the stevia plant in much the same way that sugar is extracted from sugar beets and sugar cane.

Stevia has been used for centuries as a sweetener by the indigenous people of Paraguay and central South America.

Curious about stevia?

Are you curious about stevia and steviol glycosides? We develop stevia extracts for different sorts of food. Take a look at our range of services or contact us if you want to know more about how we can help you.

Please, share this article if you liked it.

[et_social_share]