Business development • Nutri-Score is a front-of-package (FOP) nutrition label used in France, Germany, Spain and four other European countries. The label is supported by several multinational food companies and large retail chains. It is backed by science and endorsed by the World Health Organisation (WHO). So when the European Commission started looking for an EU-wide FOP nutrition label, many thought the race was already over. But European cooperation is not that simple. In this article, we tell you (almost) everything you need to know about Nutri-Score.

The European Commission has long sought an EU-wide front-of-package label to help consumers find healthier food options. The hottest candidate is the Nutri-Score, which uses a rating from A to E to indicate how healthy or non-healthy a product is in its category. So how does Nutri-Score work? Will it be introduced across the EU? What are the alternatives? We take a look at all this and much more in this article.

What is Nutri-Score

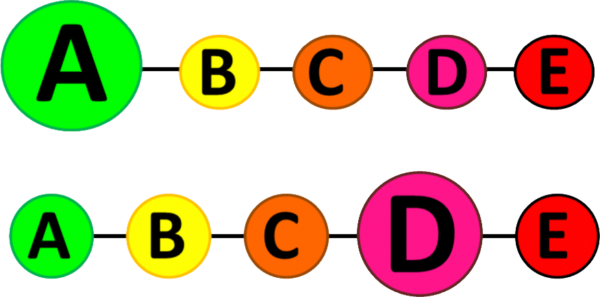

Nutri-Score is a label that guides consumers to choose healthier foods. The label is placed on the front of food packages so that consumers can quickly read it in stores. The label has a five-point scale with letters from A to E and colours from green to red. The nutritional value of the food is shown on this scale by highlighting a letter/colour combination.

Which letter/colour combination is highlighted is determined by a scoring scale ranging from -15 to +40 for foods and -1 to 10 for beverages. The lower the score, the better. The score determines which colour and letter a product should be labelled with.

| Nutri-Score for food | Nutri-Score for beverages | Nutri-Score labelling |

|---|---|---|

| -15 till -1 | -1 |  |

| 0 till 2 | 0 till 1 |  |

| 3 till 10 | 2 till 5 |  |

| 11 till 18 | 6 till 9 |  |

| 19 till 40 | 10 |  |

How Nutri-Score is calculated

Nutri-Score is calculated as the difference between a favourable component P and an unfavourable component N:

Nutri-Score = N – P

The unfavourable component N is determined by the amount of

- calorie intake per hundred grams,

- sugar content,

- saturated fat, and

- salt content.

The product is given a rating between 0 and 10 for each of these categories. The greater the quantity, the greater the value. N is the sum of these values. N can therefore vary between 0 and 40.

The favourable component P is determined by the amount of

- fruit, vegetables, legumes (including pulses), oilseeds, rapeseed, walnut and olive oil (but not potatoes, sweet potatoes, taro, cassava and tapioca and other starchy foods),

- fibre, and

- protein.

The product is given a rating between 0 and 5 for each of these categories. The higher the amount, the higher the value. P is the sum of these values. P can therefore vary between 0 and 15.

If N ≥ 11, the protein content shall be excluded from the calculation of P if

- P without protein is less than 5 for food, or

- the protein content is less than 10 % for beverages.

No rule without exception

There are specific rules for certain products:

- Cheese: The protein contribution shall not be excluded.

- Mono-products from oil, butter or fat: Nutri-Score increases from 0 to 10 with increasing proportion of saturated fatty acids to total fat. If the ratio is less than 10, the Nutri-Score is 0 (good). If the ratio is 64 or more, the Nutri-Score is 10 (bad).

- Drinks: Nutri-Score ranges from -1 to 10 depending on energy density, sugar content and percentage of fruits, legumes, pulses, nuts, rape, walnut and olive oil. Only water gets a Nutri-Score of -1 (best). For a drink to get 0 on the Nutri-Score (second best), it must have 0 kcal, 0 g of sugar and no more than 40 per cent fruits, legumes, pulses, nuts, rape, walnut and olive oil. If 100 g or 100 ml of a drink contains more than 270 kJ or more than 13.5 g of sugar or more than 80 per cent fruits, legumes, pulses, nuts, rape, walnut and olive oil, it scores 10 on the Nutri-Score (worst).

In addition to the above, there are a lot of subtleties in the Nutri-Score calculation, such as milk, drinkable yoghurt, flavoured drinks, chocolate milk drinks containing more than 80 per cent milk, soups and gazpacho and plant-based drinks not being counted as drinks.

See full details in Nutri-Score Frequently Asked Questions from the French public health authority, Santé Publique France. They also provide a spreadsheet in English for calculating Nutri-Score.

Sugar and the Nutri-Score

When calculating the Nutri-Score, all monosaccharides (e.g. glucose and fructose) and disaccharides (e.g. sucrose) are counted as sugar. This includes both added sugars and sugars that occur naturally in ingredients.

Fruit juices and the like that are added to increase sweetness must not be included in the calculation of the beneficial nutrient component (P) of the Nutri-Score.

The Nutri-Score thus reveals attempts to portray a product as healthier than it is through claims such as ‘no added sugar’ or ‘less sweet’. It works in practice. A study at the University of Göttingen, Germany, has shown this.

Nutri-Score counters misleading health claims

In October 2020, they conducted a survey with 1,103 participants. The survey asked participants about their perceptions after seeing pictures of packaging for three hypothetical products – instant cappuccino, chocolate muesli and an oat drink – with different combinations of sugar claims and Nutri-Score labels.

A statistical analysis of the survey results showed that when there was no Nutri-Score, reduced sugar claims misled participants into believing that the hypothetical products were healthier than they actually were. However, the presence of the Nutri-Score counteracted these effects and reduced the misperception of how healthy less nutritious foods were.

Nutri-Score has an effect

Is Nutri-Score effective beyond countering misleading health claims about sugar?

To answer this question, researchers at the Toulouse School of Economics and elsewhere conducted a study that examined the impact of four different front-of-pack nutrition labels, including Nutri-Score, on the purchasing behaviour of French people.

They put 1.9 million labels on 1,266 food products in four categories in 60 supermarkets. They then analysed the nutritional quality of 1,668,301 purchases using a nutritional profiling system developed by the UK Food Standards Agency.

The result?

Nutri-Score was found to have the most significant positive impact of all the labels studied. Nutri-Score increased purchases of foods in the top third of nutritional categories by 14 per cent. However, the overall effect was not as significant as in comparable laboratory studies; Nutri-Score had almost no effect on purchases of foods of poorer nutritional quality or foods that were not labelled.

The French researchers conclude their article with an interesting comment: ‘Given French attitudes towards food, it remains uncertain whether these results would apply in other countries.’

Nutrition labelling in the EU

In the European Union (EU), nutrition labelling is regulated by Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. According to the regulation, member states may recommend (not impose) a nutrition label that food business may use in addition to the mandatory nutrition declaration. This is provided that the label meets seven requirements:

- The label must be based on sound and scientific consumer research and not mislead the consumer.

- The label must be developed in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders.

- The label should help consumers understand the energy and nutrient content of the food.

- The label should have scientific evidence that consumers understand it.

- The label should be based on the EU recommended daily intakes for vitamins and minerals or, where these do not exist, on generally accepted scientific advice on energy or nutrient intakes.

- Labelling should be objective and non-discriminatory.

- The labelling shall not impede the free movement of goods.

Several EU countries use this option to recommend a front-of-package nutrition label. France is one of them.

French initiative

In July 2013, the French Minister of Social Affairs and Health mandated a working group to propose measures to help consumers make healthier food choices. In the autumn of 2013, the group, chaired by Professor Serge Hercberg of Sorbonne Paris North University, proposed 15 actions.

Action number two of the proposal reads:

Set up a single nutrition information system on the front of food packaging…

The proposed system, which had no name at the time, consists of two parts – scoring and labelling.

After the French bureaucratic and political mills had finished grinding, the actions were incorporated into the French Health Law of 2016. This included the introduction of ‘a single system of nutritional information on the front of food packaging’. But details remained to be worked out before it could be launched.

Scoring scale

The scoring scale is based on a model developed in 2004-2005 to determine which foods are not suitable for marketing to children.

It was OfCom – the UK’s broadcasting regulator – that needed a simple method to determine whether food is ‘unhealthy’ and should not be marketed to children. They asked the US Food Standards Agency for advice. They, in turn, commissioned the British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group at Oxford University to develop a model for nutrient profiling. The result was The Nutrient Profiling Model.

It is this model that Serge Hercberg and his team propose to use, with some adjustments for French conditions.

The label

While it was easy to agree on the scoring scale, it was all the more challenging to agree on the labelling. Already in the proposal to the French Minister of Social Affairs and Health, there was a sketch.

The work on the final graphic design of the label was lengthy, involved several stakeholders in a consultation process and had many controversies. After comparative studies of the perception, understanding and use of different front-of-pack labelling strategies, a label was finally agreed.

Nutri-Scores victory march through Europe

In March 2017, the French Minister of Health finally announced the new nutrition label – now called Nutri-Score.

Nutri-Score was quickly adopted by other European countries. Today, it is recommended by the authorities in seven countries:

- France (2017)

- Spain (2018)

- Belgium (2018)

- Germany (2019)

- The Netherlands (2019)

- Switzerland (2019)

- Luxembourg (2020)

Major food companies, such as Nestlé, Danone and Fleury Michon, have also endorsed Nutri-Score.

And some of the world’s largest retailers, including Auchan, Carrefour and Ahold Delhaize, use Nutri-Score on their private-label products.

Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) gives Nutri-Score a thumbs up.

EU-wide FOP nutrition labelling

It is fair to say that Nutri-Score is on a triumphal procession through Europe. So when the European Commission in 2020 started work on the introduction of an EU-wide FOP nutrition label, you’d think it was already a done deal: Nutri-Score would become the EU-wide FOP nutrition label.

But no!

Italy, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Latvia and Romania have several critical comments. Among other things, they demand that an EU-wide FOP nutrition labelling

- should not provide an overall evaluation of the food, but factual information on the individual nutrients contained in the product

- consider food as part of the wider context of the daily requirements of a healthy diet, encourage variety, moderation and a correct balance between all food groups

- take into account the specificities of each Member State’s food culture, typical diet and national nutritional guidelines

- shall exclude products with a protected designation of origin or geographical indication, traditional specialities and olive oil and other single-ingredient products

New player at the last minute

To add insult to injury, in February 2022 the Italian government launched a counter candidate to Nutri-Score: their own NutrInform Battery.

The Italian Minister for Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policy, Stefano Patuanelli, explains this by saying that Italy ‘cannot accept the trend towards a model of homologation of agri-food products’.

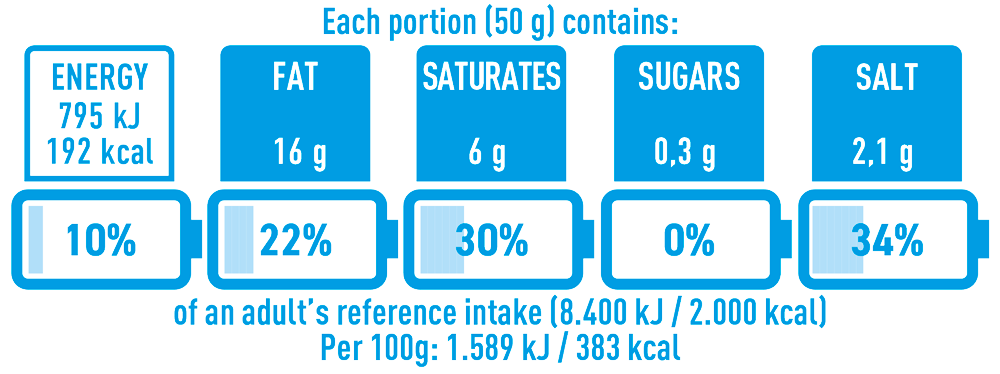

Unlike Nutri-Score, NutrInform does not provide guidance on how healthy or unhealthy a food product is. It is left to the consumer to decide. Instead, the amount of energy, fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt of a single portion is indicated. Its share of the recommended daily intake is also given as a percentage. This is also illustrated by symbols showing batteries with different degrees of ‘charge’.

The future of Nutri-Score

The European Commission, which was due to make a proposal on EU-wide front-of-package nutrition labelling in autumn 2022, now hopes to make a proposal in the first half of 2023.

Will they propose Nutri-Score? No, probably not.

‘Nutri-Score is one of the front-of-pack nutritional labelling systems, and there are several of them, but this does not mean that our system will be based on Nutri-Score’, says Roser Domenech Amado, acting head of One Health at the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Health and Consumers.

‘The different options which the Commission will put forward will build on already existing formats already developed in the European Union, such as Nutriscore, NutrInform Battery label, or the Keyhole’, says a spokesperson for the European Commission.

Time will tell.

Please, share this article if you liked it.

[et_social_share]