Product development • Aspartame (E 951) is one of our most common sweeteners. It is also one of the most researched ingredients out there. Nevertheless, aspartame can not shake off its bad reputation. Why is that?

In our series ‘Guide to artificial sweeteners’, we start with one of the most famous sweeteners available: aspartame. Aspartame has become something of the industry’s ‘bad boy’ or scapegoat. Perhaps it is a symbol of consumers hesitation about artificial sweeteners in general. At the same time, ‘sugar-free’

is increasingly in demand. How is it all connected, and what is the solution?

Aspartame – a discovery by chance

The year is 1965 and James Schlatter is a young chemist at the pharmaceutical company DG Searle & Co. He is working on developing a new medicine for stomach ulcers and has no idea that he will soon lay the foundations for a revolution.

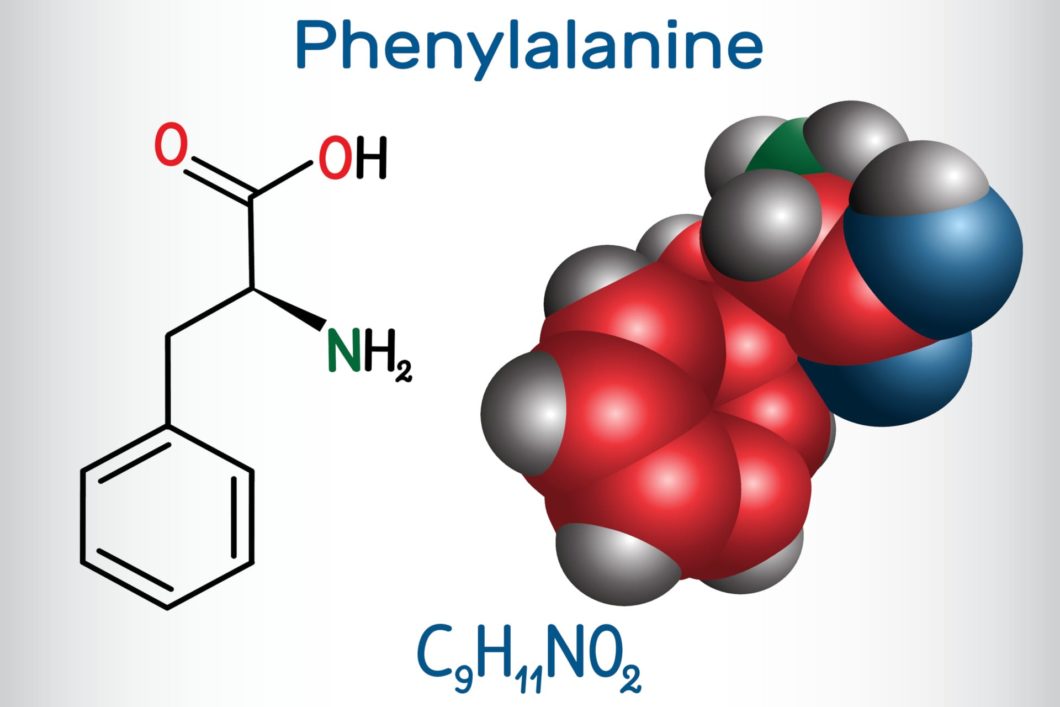

One day he is standing in his laboratory with a mixture of the two amino acids phenylalanine and aspartic acid. For some reason (which he himself has not been able to explain) he puts his finger in the mixture to taste it.

What happened then? In an interview with the Washington Post several years later, he says:

– I licked my finger and it tasted good.

There and then, the idea was born for the sweetener aspartame, which still consists of these two amino acids.

Aspartame consists of two amino acids

Amino acids are the building blocks that form proteins. Protein, in turn, is used to build cells, muscles and hormones, and more in your body.

There are about 20 amino acids that make up protein. Nine of these amino acids are called essential. That means you have to have them, they are necessary for you, but your body cannot form them by itself. You have to get them through your diet. One of these essential amino acids is phenylalanine, which is found in aspartame.

The non-essential amino acids are also necessary for us. They are called non-essential because the body itself can manufacture them when needed.

One of these non-essential amino acids that the body can produce itself is aspartic acid. It is the second amino acid found in the sweetener aspartame.

How to make aspartame?

You start by creating the raw material, the two amino acids phenylalanine and aspartic acid. This is done by culturing the bacteria Brevibacterium flavum and Corynebacterium glutamicum, which in turn produce amino acids.

Here’s how: Bacteria are fermented in a nutritious soup, stirring constantly for several days. At the same time as the bacteria grow and become more numerous, they form large amounts of amino acids.

When it’s time to harvest, the soup is put in a centrifuge that separates the amino acids from the bacteria. The amino acids are then placed in an ion exchanger, where you can pick out (isolate) the desired amino acids for further processing.

The next step in the process is to place the amino acids in a crystallization reactor, where crystals formed during the process are centrifuged away. Then the amino acids are allowed to dry.

Then comes the synthesis – bringing the amino acids together to create aspartame. This takes place in several steps, where, among other things, the amino acids are heated to 65 degrees and then cooled down to -18 degrees. Then new crystals are formed which are mixed with acetic acid, hydrogen and palladium under high pressure for 12 hours. This causes the two amino acids phenylalanine and aspartic acid to fuse together.

The whole process ends with further purification where the added substances are filtered and distilled. What remains is a hard mass which is dissolved with ethanol, after which the amino acids are crystallized again, filtered one last time and then allowed to dry.

A crooked path to success

When James Schlatter licked his finger in 1965, he had no idea it would change his whole life. Instead of developing a medicine for stomach ulcers, he had discovered an artificial sweetener that many years later would turn over hundreds of millions of dollars a year. But getting there was not an easy task and fraught with controversy.

In 1973, an application was made to the FDA (US equivalent of the National Food Administration) to use aspartame as an additive in food. Together with the application, the company sent Searle 150 studies, and a year later, in 1974, aspartame was approved, albeit with certain restrictions.

In 1983, aspartame was approved as a sweetener in soft drinks, which laid the foundation for a revolution in ‘light’ beverages. It was the big breakthrough for aspartame.

But right from the start, in the early ’70s, the FDA’s decision to approve aspartame as a food additive was criticized by Dr John W. Olney and the author of The Chemical Feast, James S. Turner, who had researched the effect of amino acids on the brain.

They questioned the safety of aspartame and pointed out, among other things, that people with the disease phenylketonuria (PKU) can not break down the amino acid phenylalanine, which is found in aspartame.

This opened up a wide range of studies on aspartame. It has made aspartame one of the most researched ingredients in the world.

Is aspartame dangerous?

Today, the Swedish Food Agency recommends that people with the disease phenylketonuria (PKU) should be careful with their intake of phenylalanine, especially children.

Otherwise, there are no restrictions as long as we stay below the recommended dose. On the Swedish Food Agency’s website, we can read:

‘Aspartame-sweetened soft drinks may contain a maximum of 0.6 grams/litre. This means that a person weighing 60 kg can drink four litres of aspartame-sweetened soft drink/day.’

Over the years, studies have emerged that point to an increased risk of cancer with a large intake of aspartame. Some of these studies have been widely circulated in the media, which is one reason why many consumers are hesitant about aspartame.

The EU’s equivalent to the Swedish Food Agency is called EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). According to them, these studies have had major shortcomings and unreliable results. On the Swedish Food Agency’s website, we can read:

‘All studies involve lifelong exposure to doses up to 8 g aspartame/kg body weight and day. This dose, converted to an adult, is equivalent to approximately 2,400 cans of aspartame-sweetened soda each day throughout life.’

Sceptical consumers

Although numerous studies have shown that aspartame poses no danger nor serious side effects, many people claim that they do not tolerate aspartame. Common symptoms are headache, dizziness, fatigue and mood swings.

The research done in this area has not been able to demonstrate such a connection. At the same time, researchers cannot completely rule out the possibility that individuals may have increased sensitivity to aspartame.

In a double-blind test conducted by researchers from several different universities, mainly in the UK in 2015, 48 people who said they were sensitive to aspartame ate two bars at one-week intervals, some contained aspartame and others did not. Results showed that there were no differences in symptoms between those who ate aspartame and those who did not.

In 1984, The Center for Disease Control (CDC) conducted a four-month study of about 500 individuals. The participants had various ‘general problems’ with their health, but nothing that the study could link to the use of aspartame.

Despite the fact that ‘food agencies’ around the world have declared aspartame safe, there is still a great deal of uncertainty left. The scepticism comes, among other things, from financial connections between industry and authorities and suspicions of bribery.

If you delve into the simplified description above on how to make aspartame, you will find another explanation for consumer scepticism. It is a product invented in the laboratory and manufactured in a factory.

Applications

Within the EU, aspartame is used in a number of different products, including beverages, desserts, ice cream, sweets, chewing gum, yoghurt, breakfast cereals, jams, sauces and dietary supplements.

Benefits

Aspartame is as high in calories as sugar (4 kcal per gram), but in practice, it is basically free of energy. Because it is 180-200 times sweeter than sugar, small amounts are needed to give the same sweetness as sugar. The taste is sweet but not bitter.

Disadvantages

Aspartame is a compound of several amino acids. When the pH value becomes too high or at high temperatures, the amino acids go their separate ways and the sweetening effect disappears. In practice, this means that aspartame is unsuitable in baking or in foods that require long shelf life.

If you despite this, use aspartame in baking, you may need to add other ingredients to keep it stable. Fat or maltodextrin may work to some extent. In products that require long shelf life, you need to add other ingredients to ensure the quality of the food. To improve the shelf life of soft drinks, saccharin can be used.

The bad reputation persists

Although research systematically dispels myths and negative notions about aspartame, the dubious rumour remains. Therefore, from a marketing perspective, it is difficult to argue for aspartame, at least if you want to clearly strengthen your brand.

Consumers prefer foods that are perceived as natural or at least do not contain anything unnatural. A close relative is the global free from-trend, which means reducing or removing ingredients that, for various reasons, are not in line with the norms and preferences that many consumers have.

But there are alternatives to aspartame that come from natural sources: sweet steviol glycosides, which are extracted from the stevia plant.

It is a calorie-free alternative that does not raise blood sugar levels and can be used in a variety of foods. And unlike aspartame, steviol glycosides have not faced the criticism that aspartame has endured.

The future is natural

The development of better steviol glycosides in recent years has been at a furious pace as we have become better at extracting the rare steviol glycosides with the most sweetness, such as Reb M.

In the coming years, we will probably see more innovative combinations of sweeteners of natural origin.

An example is thaumatin. Thaumatin is a high-intensity sweetener that originates from the West African Katemfe fruit. It creates synergy effects with steviol glycosides, which enhances the sweetness and overall taste experience.

Curious about stevia?

Are you curious about stevia and steviol glycosides? We develop stevia extracts for different applications. Take a look at our range of services or contact us if you want to know more about how we can help you.

Please, share this article if you liked it.

[et_social_share]